By Rohan D. ‘25

Using Ozempic to lose weight has captivated America, even causing widespread shortages of the drug across the country. While the drug has primarily been considered an option for adults struggling with obesity, interest in using the drug in teenagers grows, and with good reason. Obesity rates among teenagers have been steadily rising, leading to an increased risk of various health problems, including heart disease, diabetes, and mental health issues. A JAMA Pediatrics report estimated that the prevalence of obesity among US children aged 12-19 was 25.6% in 2020. Furthermore, adolescents with obesity are very likely to remain so as adults, with Simmons and colleagues showing in 2015 that 80% of adolescents with obesity will still have obesity into adulthood.

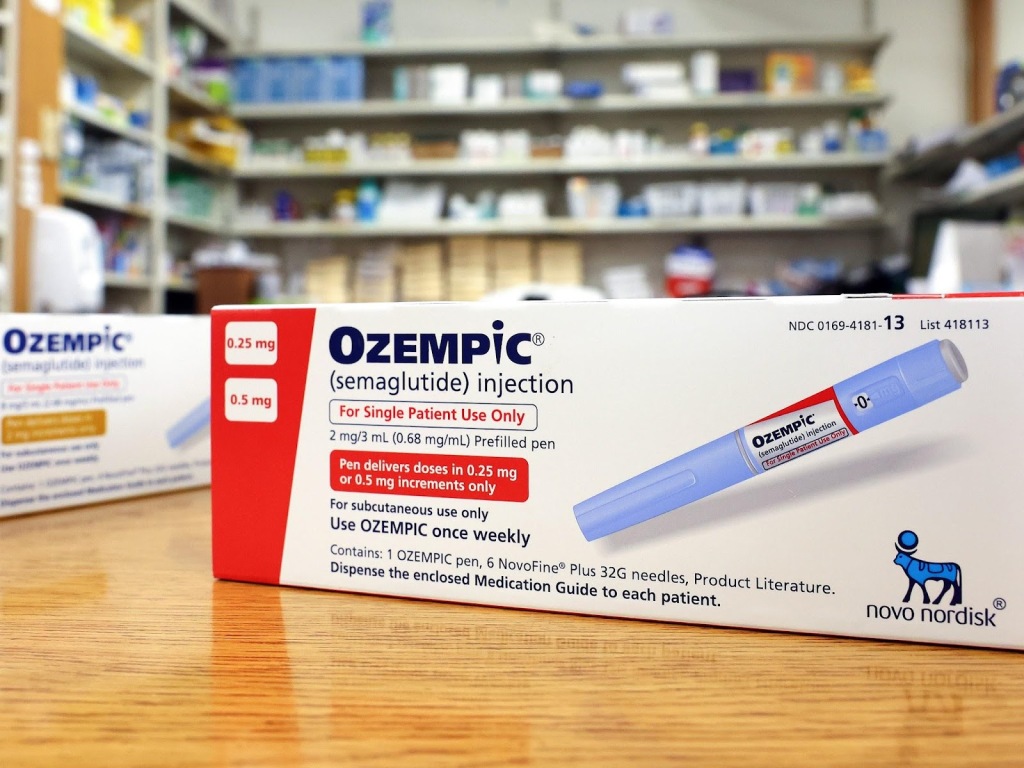

The traditional cornerstones of weight management have been a modification of diet and physical activity. However, these interventions’ generally dismal lack of efficacy is well understood; it is exceptionally difficult to lose weight and maintain it simply with diet and exercise. The tides are now turning due to the introduction of a new class of drugs called GLP-1 analogues. Ozempic and its lesser well-known form Wegovy are brand names for semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogue. GLP-l analogues help regulate appetite and reduce food cravings by making patients feel “full” faster, leading to weight loss. Positive weight loss outcomes in adults prompted researchers to consider its potential use in adolescents suffering from obesity. In December last year, the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) reported that adolescents with obesity who were randomized in the Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with Obesity (STEP) TEENS trial to receive semaglutide over 68 weeks had a 16.7% decrease in body mass index (BMI) compared to those taking the placebo. This raised the possibility that Ozempic is even more effective in teenagers than it is in adults. Furthermore, these reductions in body weight were associated with early suggestions of improvement in the health of the heart, liver, and other vital organs.

The usage of Ozempic in adolescents with obesity is not without risk. In the NEJM’s randomized trial, the incidences of gastrointestinal adverse events, such as nausea and vomiting, were greater with semaglutide than with placebo (62% vs. 42%). One risk of intense interest in any possible exacerbation of eating disorders; this is important because eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia can begin in adolescence and are often precipitated by weight stigma and dieting. However, there was no difference between the semaglutide and placebo arms regarding mental health status, and the number of psychiatric adverse events was lower in the semaglutide arm than in the placebo arm.

But there are also the risks that cannot be precisely estimated. Prior weight loss drugs like fenfluramine, the “fen” in “fen-phen,” have had to be recalled when long-term side effects were noted after the small clinical trials end. Because of heart valve damage, American Home Products Corporation agreed to pay $3.75 billion to the 6 million people who took fenfluramine. Furthermore, clinical trials can only characterize the safety of an intervention for a finite period. The safety of Ozempic usage beyond the time periods studied in clinical studies is poorly characterized. As the obesity management paradigm shifts from simply using Ozempic to induce weight loss over one to two years to “maintenance” strategies where patients are treated potentially forever, the lack of information about long-term use of Ozempic may become more consequential.

Nevertheless, the number of teenagers with obesity and the associated revenue opportunity have attracted the interest of the pharmaceutical industry. In December 2022, Novo, the manufacturer of Ozempic, received U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for treatment of teenagers with obesity. Subsequently, the American Academy of Pediatrics moved from “watchful waiting” to recommending pharmacotherapies like Ozempic as a treatment for adolescents with obesity. With FDA approval and the nod of prominent medical societies, Novo now has the imprimatur needed to let the tsunami of interest among obese adults reach their teenage counterparts.

Mr. Akash Tewari, a biotechnology stock analyst at Jefferies, believes that the current generation of weight loss drugs, including GLP-1 analogues, represents a pivotal moment in the drug development industry. Escalating rates of obesity increase the risks of type 2 diabetes and liver diseases like non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), each of which is itself very costly with the potential for severe long-term health issues, including the need for surgeries such as limb amputations and liver transplants. In an exclusive interview with the Gryphon Gazette, Mr. Tewari stated, “Because there is such a significant unmet need and because you are staving off costly disorders by losing weight, we need to consider a more aggressive use of the drug.” Specifically regarding usage of GLP-1 analogues in the adolescent population, Mr Tewari stated, “How can we save the most American lives? Many diseases that are downstream of obesity are linked to our cardiovascular health. We need to consider GLP1s as a more aggressive tool to use in the adolescent population.”

The pharmaceutical opportunity in adolescents with obesity is also enticing companies that are seeking novel mechanisms of action different from Ozempic. Dr. Mani Subramanian, CEO of Orso, stated in an exclusive interview with the Gryphon Gazette, “Obesity is the pandemic that is affecting the globe.” Affecting everyone with high levels of childhood obesity in elementary, middle, and high schools, “obesity is something that the World Health Organization is taking seriously.” He also noted that “Mitochondria in teens works very well,” meaning that an adolescent will lose weight more effectively when one exercises than an adult. This invites the question of whether enhancing energy expenditure with drugs in the obese adolescent population may be a uniquely successful weight loss strategy compared to simply reducing caloric inputs with a GLP-1 analogue. Weight loss therapies for adolescents, when appropriately evaluated with well-conducted clinical trials, may be transformative for teenagers, Dr. Subramanian proclaims. “One should not focus on being skinny; one should focus on being healthy.” Furthermore, “Medications have a very clear role in helping obese teens to move the needle significantly. When you lose weight, it improves your physical functioning, quality of life. If you address this early on in life, it will be easier than if you don’t do it as a teen.”

Although there will be critics, it is inevitable that Ozempic’s visibility as a weight loss agent will grow among teenagers. Indeed, it may already have happened in the Bay Area. Teenagers can be differentially vulnerable to societal pressure and media-driven ideals of body image, excessive weight leading to a cascade of low self-esteem, depression, and body image concerns. In an exclusive interview with the Gryphon Gazette, Dr. Nisha Patel, an internal medicine physician, Director of the Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Clinic, and Chief Wellness Officer at California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco states, “Adolescence is a really tender period in life, and self-esteem can decrease significantly, so there is definitely potential for abuse. There is a subset of adolescents that might be using Ozempic like this, but it’s not supposed to be used for cosmetic reasons; it is supposed to be used to improve the quality of life of those who really need it.”

Dr. Patel also notes a rise in the use of semaglutide in the adolescent population, especially because insurance companies are starting to cover it. However, Ozempic and Wegovy are brand names of semaglutide; they are the same medication but FDA-approved for two different indications. Because of the national shortage of Wegovy (approved for weight loss management), Ozempic (approved for diabetes) is being used “off-label.” When this occurs, insurance does not cover the medication. Therefore, patients who wish to use it may have to pay nearly $1300 per month out of pocket. This highlights the socioeconomic disparity of the drug’s availability and usage. “We are only treating a fraction of adolescents,” Dr. Patel says.

Finally, at Crystal, Ms. Patti Syvertson, Director of Sports Medicine and the Mind Body Department Chair, states in an exclusive interview with the Gryphon Gazette, “Body mass index (BMI) might not be the most accurate way to assess obesity as there are many factors that can skew it (i.e., a very muscular short individual may have an elevated BMI).” Instead, she adds, “Body composition might be better measured via a DEXA (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) scan. It is a medical imaging study that can provide the person with an in-depth analysis of adipose tissue, muscle mass, and bone density.” She goes on to emphasize, “Our goal over the three years in the Upper School curriculum is to teach our students healthy habits of body and mind. By the time they leave Crystal, we have hopefully armed them with enough information and knowledge to make very wise choices.”

Ultimately, Ozempic is a drug, but also a phenomenon. As a pharmacotherapy, it may offer patients an unprecedented opportunity to break the code of obesity, resulting in multiple health benefits as the downstream sequelae of obesity melt away. However, the experience with Ozempic in adults suggests rampant usage well beyond people diagnosed with obesity. In the adolescent population where the least is known about the risk profile of the drug, a collision awaits with loose usage motivated by aesthetic desires rather than disease modification. A new chapter on obesity awaits.

Leave a comment